I turned 40 last month.

I celebrated hard. My partner and I went out for a fancy dinner; I spent a lazy seven hours schvitzing away my youth at a local spa; and I threw a party for all my friends.

I’m not normally one to make a big fuss about my birthday, but this year was different. Yes, because it was a landmark birthday—but more because I never thought I’d live to see 40.

I’ve shown symptoms of depression since I was a preteen; in adulthood, additional diagnoses of an anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been added to the mix. (I’m an overachiever, okay?)

I work really hard to manage my symptoms. I consult with both a therapist and a psychiatrist, and I take my meds religiously. Nonetheless, my life has been punctuated by multiple depressive periods, some of which have been marked by intense suicidality.

It is exceptionally difficult to explain suicidality to someone who has never experienced it. For me, it’s like standing at the end of a dock on a dark and foggy day. My back is to the water, so I can see the path ahead of me; but it’s so shrouded in fog that any step forward would require a leap of faith. Instead, I fall backwards into the water.

I begin to sink. While my instinct is to fight, both my mind and body succumb to the pressure and accept the seeming inevitability that I am going to die. And so I stop fighting, and let myself disappear into the depths.

It’s a constant state of fight-or-flight, which is exactly as exhausting as it sounds. And because all of your mental resources are directed towards your own survival, everything can seem like a threat—including the people you love.

Just ask my partner. On our first date some 5+ years ago, I spoke very openly about my history with depression and the ways it could impact a potential partnership. Fast forward to last year, when we moved in together and I promptly fell into a severe depressive episode that we suddenly had to navigate fulltime as a team.

During these episodes, I’m immensely prone to anger outbursts. While the term itself sounds dry and clinical, the reality is much darker. I become highly agitated in the span of seconds, resulting in yelling, physical agitation, aggression, and deeply hurtful language. There doesn’t even need to be an external trigger; the chaos within is sufficient.

Pathetically, I used to take pride in my ability to land a gut punch on the people I loved most. It felt protective, because I was already struggling so badly that I didn’t believe I could survive another pain point.

Even worse than feeling pride, I used to feel JUSTIFIED. Not necessarily for hurting people, but certainly for expressing my own pain in a way that demanded to be seen.

I know better now. I’ve heard both of my children call me “scary” after I raised my voice. I’ve seen the utter devastation in the eyes of my loved ones who have just been decimated by my words. I’ve seen it in my own eyes when I look in the mirror afterwards—a monster reflected back at me.

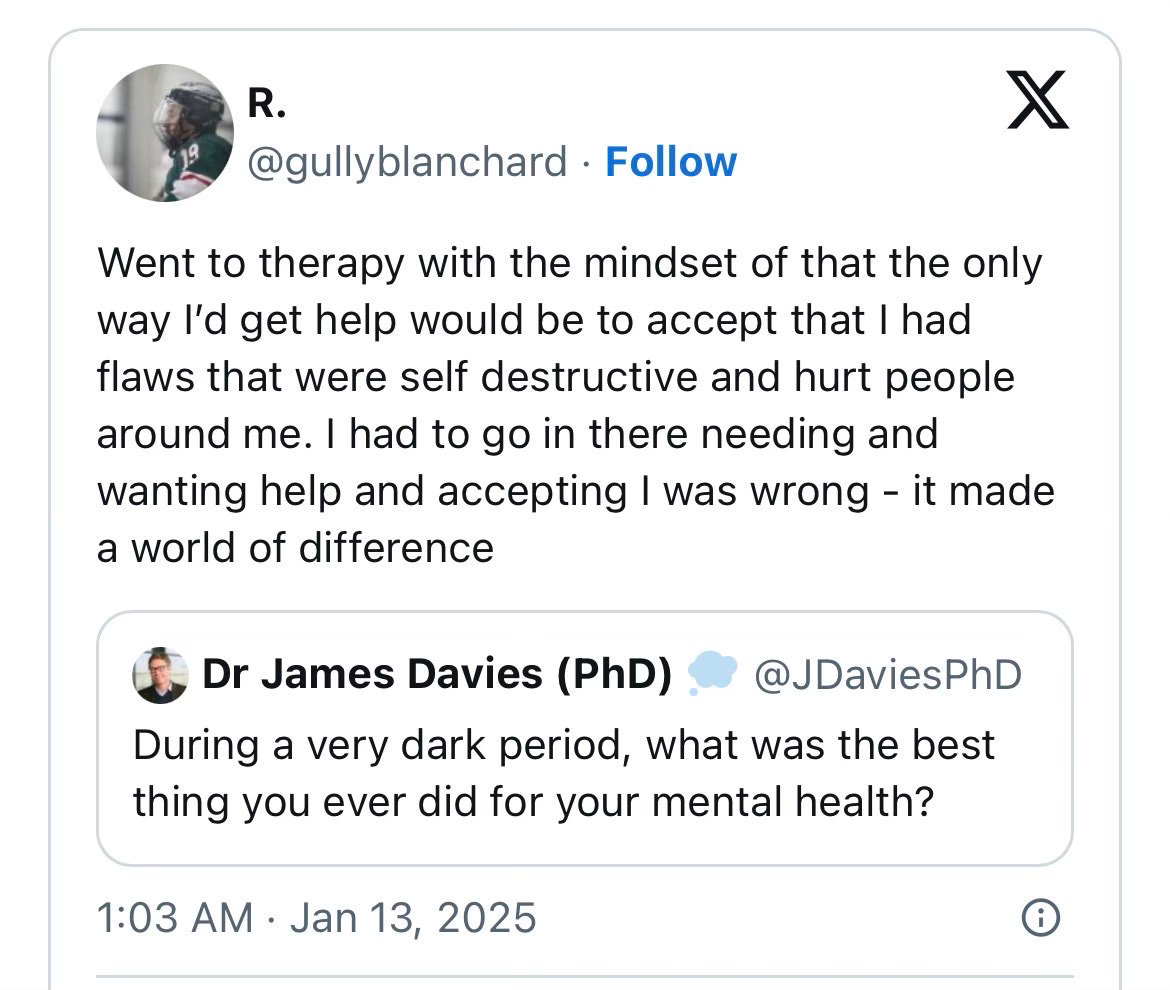

So I put in the work, both independently and with the guidance of mental health professionals. After years of targeting this practice of mine, my anger outbursts are less frequent and severe. I’m able to identify when they’re happening, find healthy ways to intervene, and repair more easily with the people who love me.

It’s a gift, and one I’ve worked hard for.

The irony is that lately, I find myself in the unenviable position of both watching and experiencing my peers engage in the same self-protective practice—the boxer becomes the punching bag.

I don’t begrudge those who are struggling their feelings. Take, for example, the volunteers who have supported Afghans since the fall of Kabul. This community is suffering immensely. My colleague Rebecca Santana describes it better than I ever could

They have assisted Afghans struggling through State Department bureaucracy fill out form after form. They have sent food and rent money to families. They have fielded WhatsApp or Signal messages at all hours from Afghans pleading for help. They have welcomed those who have made it out of Afghanistan into their homes as they build new lives.

For Americans involved in this ad hoc effort, the war has reverberated through their lives, weighed on their relationships, caused veterans to question their military service and in many cases left a scar as ragged as any caused by bullet or bomb.

Most are tired. Many are angry. They grapple with what it means for their nation that they, ordinary Americans moved by compassion and gratitude and by shame at what they consider their government’s abandonment of countless Afghan allies, were the ones left to get those Afghans to safety.

And they struggle with how much more they have left to give.

Here’s where I can supplement Rebecca’s writing, because I know the answer to that question: the volunteers have nothing left to give. They have sacrificed so completely that most have lost jobs, money, relationships, time, and faith. They are in survival mode, and I know better than anyone how that goes.

But I also know the ways in which such anger can consume you, moving through your life like a wildfire that leaves nothing but destruction in its wake.

To my peers who find themselves walking a similar path to my own: please learn from my mistakes. You are a victim of your own mental health; your sense of abandonment and outrage is wholly justified.

But being a victim is not an excuse to victimize others, no matter how protective or satisfying it may feel.

We need look no further than our current social climate for evidence of what happens when basic kindness and decency degrades. The recipients of anger outbursts bear these memories like scars, which will fade in time but never heal. Instead, there is lasting damage to their nervous system, convincing the victim that neither you nor the world around them is safe. This then contributes to their own psychological pain, causing them to question their deservedness of abuse or seek refuge in their own sense of injustice at the way they’ve been treated. Naturally, this can increase their own anger, such that the cycle continues.

And let’s be real: anger outbursts can have devastating consequences for the perpetrators, too. While I can attest that these outbursts offer temporary relief, the subsequent emotional fallout is a poison that eliminates your sense of worth and most sacred relationships, causing you to misunderstood, resentful, and alone. As Nelson Mandela once said, "Resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies."

So take it from my own lived experience: it’s okay to struggle and it’s okay to be angry about that. But there is nothing right or righteous about taking that out on the people who love you most.

Because one day you’ll turn 40, and it’s far better to look around the room at all the people you love than all the bodies you’ve left behind.